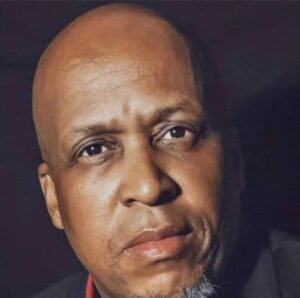

By: Clyde N.S Ramalaine

The Patriotic Alliance, one of South Africa’s promising small parties, recently had its inaugural Conference in Qeberha. At such Conference, a raft of policy decisions was concluded. Yet none of the many rivaled its undeniable adopting of the LGBTIQ+ League policy decision, a first in the body politic of South Africa. This one attracted the most interest in comments if social media streets make up the yardstick.

I was hoping you could permit me to say something about the undeniable growth, in some instances, role far beyond its size the Patriotic Alliance plays in SA political space. Those who often condemn the PA, be they former members or ‘saamlopers,’ will tell you Gayton McKenzie listens to no one, and he is, therefore, a proverbial lord unto himself. Whether this statement is correct is only essential if you locate the subject of the PA’s success and growth. So the issue of democratic leadership I would advance must be placed at the interstice of existence and success for the PA. The PA’s success is precisely because of what some may define as a dictatorial style and the presence of its president. So if you expected the PA to be an internal democratic party where things are reached by consensus or put to a majority vote, you would not have understood its success factor. Some contend that if something works, why fiddle with it? The quest for more pronounced growth tends to fidget with what we think works as our success.

There is thus a dialectical tension between the hitherto success of the PA and its quest to grow further in which the person and being of its president must be centralised. I will return to this balancing act that increasingly will necessitate an institutional presence instead of an individual personality presence.

In the aftermath of this organisational historical gathering, social media, and pastoral chat, groups are flooded with comments, critiques, and jaundiced unhappiness. I see all of this as needing more honest reflection. The hullabaloo around the PA’s adoption of members from the LGBTIQ+ communities is misplaced if it has the offense of pastors at the centre. I, however, would suggest we divorce the debate from the feelings of mortal, fallible, and, in some instances, very ambitious clergy members.

We may argue the need for the Patriotic Alliance at its maiden and most recent National conference to create a special LGBTIQ+ league, which I believe should constitute the honest discourse.

The PA’s rationale may have been to eternalize the existence of the LGBTIQ+ in the PA, but it may have the opposite result. With eternalise, I mean it saw the need to underscore the presence of LGBTIQ+ as citizens of South Africa. This is necessarily pragmatic, even commendable, since the South African constitution and the public policy for governance in its ideals and praxis envisages a democratic, non-sexist, and non-racial society as an ANC-led reality. So while the PA intends well with its institution of a league, it may, with this act, further alienate South Africans, better understood as PA members.

This may, in scientific and theoretical language, be understood as othering. The counter-argument could be: Why does the PA see no need to form a heterosexual league – which renders the idea of a particular league informed by sexual orientation of social identity perhaps nonsensical? Singling the LGBTIQ+ community out in league frames should not be any political party’s task assignment or mission. For identifying a need to form a unique LGBTIQ+ league, the PA may inadvertently aid the ostracising of the same group.

On another score, the adoption of a specific and identifiable league in the PA is also inescapable of the notion of minority politics which has been a central philosophy of the PA from its inception. We must engage this notion of minority groups as a metanarrative in South African discourse. We are yet to encounter this construct less in emotional rhetoric or blame game antics. We warrant asking what informs the acceptable content measurements for qualification of being a minority. Minority in relation to who and what where? It cannot be that when it is convenient, the binaries of black and white become obvious choices for explaining the notions of majority and minority. We, therefore, warrant engaging minority as an adjective to describe groups in the distinction of others honestly. Having said it, I shall dare to advance the LGBTIQ+ discourse in SA, if not worldwide, comes framed in kaftans of victimhood, which is said to be engineered and maintained by an intolerant majority that automatically constitutes the villain. It is a victimhood that feeds off this minority rhetoric notion.

The African Christian Democratic Party [ACDP], at first loud and against, eventually had to open itself to the LGBTIQ+. Pastor Kenneth Meshoe learned this lesson in public space. I almost involuntarily want to caution anyone to stay clear from being duped by CHRISTIAN as that which makes for a name of a political party. I expect all political parties to be open to the LGBTIQ+ communities. My challenge for the complaining pastors – Why are you a member of a secular political party? You can decide not to be.

I stopped my membership in the ANC in 1999 when I could not reconcile myself with some of the party’s policy decisions. That is also why I will never be a card-carrying member of any secular political party. I decide whom to vote for as and when the time arrives. I am married to no political party and never will be.

So those who crucify the PA in leadership on this score must crucify themselves for having made naive assumptions about why political parties exist. Equally, I would like to read the discussion paper of the PA that led it to an LGBTIQ+ league policy adoption. Without such, one can merely surmise, which renders one to assume.

The PA will increasingly be compelled to make public its decision-making infrastructure and means for its policy decision outcomes to afford its members and those not members to engage it critically. If the PA hopes to be a significant political player, it must imbibe the necessity of documented discussion papers and policy infrastructure. Suppose it wishes to be an institution of the future. In that case, it dare not, in a monotone singularity of authority, only rely on the mind and mouth of its first member and president, Gayton McKenzie, who is human. That humanity sees him also sometimes responds, if not reacts, to cardinal issues from the proverbial obdurate hip.

Nevertheless, I am glad the PA had its first Conference since this can only mean it will become more and more a democratic organisation in which its internal structures feature not as add-ons but as central to its ideological content, policy decision, and mobility trajectory.

The pastors who are PA members have also been told that if they do not appreciate the PA decisions, the door stands open to leave. This again speaks volumes to the challenge of internal democracy as perhaps not yet a reality in this fast-growing political party. The policy should not dictate a leader’s voice unless the party, as I had advanced with the EFF, belongs to the leader. Undeniably, the PA has grown and will grow because the scope of the defect in ANC and current opposition party frames presents fertile soil for a party such as the PA.

Back to the earlier alluded notion of minority politics. The PA’s growth is also similar to all parties since it adopts race as the premise for membership at a fundamental level. In its instance, it’s the discursive ‘Coloured’ group social identity. In its search for an emerging capitalist labour force, the Colonial state sometimes defined it as the native problem, apartheid used it as a trojan horse identity, and ANC-led democracy used it to alienate punitive means of economic justice.

Race, therefore, at a fundamental level, defines all South African political parties with that. It is easy in SA to explain parties in apartheid identity markings of white, black [African], Coloured, and Indian. The late Amichand Rajbansi’s Minority Front was arguably the most ‘successful’ model since it was an ‘Indian’ party that recognised and propagated that ‘Indians’ are a grave minority, necessarily vulnerable and, therefore, can only negotiate out of such hegemonic conviction in specific spaces where Indians define a more than 50% demographic representation of the South African populace. Meaning the Minority Front existed because of and in the upkeep of apartheid racial classification. So do the ANC, DA, EFF, FF, COPE, UDM, and ATM, to name a few. Some exist in pretentious claims of religion, such as the ACDP and other Muslim premised parties. ACTIONSA pretends to be a liberal party, yet its root in ideology leans the same as the DA, notwithstanding Herman Mashaba.

Another observation perhaps worthwhile to mention here is the quest for what commonly is bandied around as inclusive growth. The PA conference, with this adoption of an LGBTIQ+ League on another front, may underscore the brewing challenge of or absence of democratic infrastructure, meaning the PA must explain its ideology of democracy as an organisational reality. It will find itself increasingly accused of non-democratic utterances, decisions and outcomes at least as a reality at an internal level. If the president did say members [pastors] can leave because they disagree, it attests to the challenge of what democracy means in the PA. Political organisations must allow for disagreement if its democratic in its central conviction and praxis.

Political Analyst, Theologian, Lifelong Social and Economic Justice Activist, Author, Published Poet and Freelance Writer.

Dankjewel