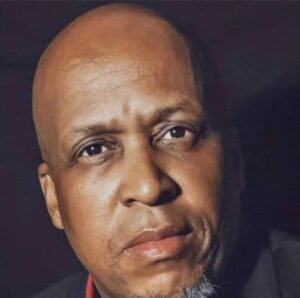

By: Clyde N.S Ramalaine

Preamble

A year before democratic South Africa’s 7th National Elections, the African National Congress hitherto entrusted to lead SA is beset by decay and effectively resigned to accepting coalitions even with the leading opposition DA as a means for governance. That decay marks an organisation and SA governance in cancer of unaccountability because it evidences an increasing trust deficit with the voters of South Africa.

To appreciate this, one may look at its election performance results for national and municipal elections as recorded from its maiden participation in elections in 1994. From inception in the Mandela era of 1994, the ANC evidenced 62,65%. Under Mbeki’s first term, it scored a 66,35%, and in the second term, the ANC in voter support showed a high mark of 69,69% in his second term. It partially declined in the first term of Zuma to register 65,9% and declined further to 62,15% in his second term. Under Ramaphosa, in 2019, the ANC registered for the first time a national elections results of 57,5%, and it is envisaged that the ANC may either make 50% or go slightly under that come 2024. Hence the idea of discussion documents on coalitions as a proactive intervention was tabled in its April NEC meeting. I however had written on this envisaged coalition as far back as 2021.

While unaccountability extends itself to organisational presence, which we in the content momentarily allude to, the central focus of this musing makes for ANC leadership in the governance of South Africa. While one can make a case for its decline by using the election results as the yardstick, we may also use public sentiment, its record of failure in service delivery, poor governance, its lack of explicit and straight-forward ideological content, its failure to give effect to economic redress, and its captured state by capital in factionalized identity and its proneness for corruption. Naturally, the ANC will respond that its problem is not a lack of service delivery but really the upkeep of the success of its delivery. That, however, is a debate for another day. To advance this observation, one could use a litany of tools, some scientific measurable in quantitative and qualitative research methodologies, others narrative in historical analysis defining a quilt of moments over the last almost thirty years of ANC leadership.

The most recent 17-page letter penned by Thabo Mbeki as addressed to current Deputy President Paul Mashatile centralizes two critical aspects, vacillating a organisational foothold with undeniable relation to SA governance and an advanced alienation resultant effect of the masses. The second but more important issue is the defence of the ANC of its President at the cost of all and anything. Yes, Mbeki wrote the letter and had his political hopes better understood in a particular agenda – he was active in the aftermath of his self-imposed exile until he found it fitting to condemn his successor presenting an analysis as a bystander, therefore, unilaterally exonerating the era of his leadership for its undeniable contribution to the state of the ANC in unaccountability.

However, all these valid rebuttals against Mbeki unfortunately cannot negate what he raised in his 17-page scathing letter to the deputy president since the President excused himself from the meeting on Phala Phala. Let us hear Mbeki as he laments in a pseudo-prophetic tone the expected result of the widening gap between the ANC and South Africans:

…To be honest to ourselves, as our Comrade President insisted, we must expect that the already existing gulf between the ANC and the people widened, as the latter saw the former refuse to investigate the alleged criminality which has resulted in these masses suffering from long periods of very destructive load shedding!

I, like many, have differed with Mbeki, as our 2010 exchanges have shown. Nevertheless, Mbeki’s intervention in the period with this lengthy letter raises pertinent issues inescapable for the ANC and its future. Chief among those is how the ANC in December 2022 abused its majority in Parliament to ensure its President Cyril Ramaphosa is not held accountable at the expense of constitutional democracy and the image of the ANC.

Mbeki asserts,

As ANC members, we would assume that our President would not do and has not done anything impeachable.

Whatever the criticisms legitimately or illegitimately against Mbeki, it would be organisational, political suicide to ignore what he says because convenient, cheap refuge is taken in the ‘whataboutisms.’ However, it would be disingenuous to look at the Ramaphosa era and cry all of what the ANC evidence came about since December 2017. That would not just be a fallacy but an attempt at rewriting history in an evanescent manner.

In this musing, one will advance the notion of a freefall of unaccountability as an ANC reality by assessing its leadership against the backdrop of situational theory. The situational leadership theory refers to leaders who adopt different leadership styles according to their team members’ situations and development levels.

At the hand of this commonly accepted definition of situational theory, we will look back on the last twenty – nine to thirty years of the presence of an ANC in SA governance and present narratives delineating epochs measurable in the leadership of Mandela, Mbeki, Zuma, and Ramaphosa to argue that the subject of unaccountability started from the first instance under a Mandela era. While situational theory, as advanced by its founders Hersey and Blanchard, identifies what the leader stands for and does and identifies the group he leads, this musing attempts to draw the borders of that leader and group identities slightly wider as better understanding the leader as representative of a particular persuasion and group as a combination of ANC members and those who make up voters for the ANC. The idea of an original situational theory uses three independent variables (problem recognition, constraint recognition, and involvement recognition) to predict the dependent variable of information seeking and processing.

One will, in this musing, advance the ANC in leadership attest to an increasingly unaccountable identity. I will identify the four consecutive eras better understood in the leadership of Mandela, Mbeki, Zuma, and Ramaphosa. I wish to postulate the distinct epochs framing the eras of “Mandela: the ANC gods of liberation dwelt among us…we were in awe…” The epoch of “Mbeki: self-styled European trained intellectual gods in supremacy...” The era of “Zuma: ‘pseudo-workers-class, populist-‘peasant’ rebellion…” against self-imposed intellectual gods. “Ramaphosa: capital-captured-unfettered-unaccountability largesse…“ translates to a mafia state of governance by vigilantism.

One will do four things; firstly, I attempt to narrate key unfoldings of the particularity of the designated eras, albeit in an adumbrated sense. Not remotely in any exhaustive sense since the focus is to argue how leadership distinguishes itself in problem recognition, constraint recognition, and involvement recognition and what the ANC members and voters permitted.

Secondly, referring to recognising the ‘problem recognition’ component, we cite classic examples of leadership to accentuate and underscore the notion of unaccountability for each period. We then ask in acknowledgment of a lack or presence of ‘constraint recognition’ the questions for each of the examples are provided. Lastly, contend the failures of ANC members, Tripartite Alliance constituencies, and South Africans to keep the respective ANC leadership accountable for their actions and inactions as the reason SA is in the proverbial cul-de-sac of gross unaccountability. This latter part speaks to the notion of ‘involvement recognition.’

Accountability is ‘the act of taking responsibility for the results of your work regardless of its success. Because accountability helps with practicing honesty. Merriam-Webster explains unaccountable to suggest not to be accounted for, not to be called to account: not responsible unaccountability in synonyms is understood to mean inexplicable, irrational, or unusual.

Throughout, we will contend that the behaviour of the leadership in conjunction with its group [ANC members and voters] defines the critical role players in such a lack of accountability. This is better understood in need to either turn the proverbial blind eye or shut up and not challenge effectively, which manifests as an ordinary subculture in these instances.

Part 001 …And the ANC’ gods’ of liberation dwelt among us, and we were in awe…

If we are going to appreciate our future, we are, of necessity, compelled to ask what the current means against the backdrop of a past we sojourned. That past for brevity’s interest and the purpose of engaging in this four-part musing consciously and for primary intentions has its genesis in 1990. The period between 1990-1999 marks a specific and very unique moment in the new history of South Africa. Notable for its uncertainty. It includes a period that culminated in CODESA talks that might be traced back to 1987 in Lusaka and Dakar talks led by white representations of business, academics and Progressive Party leaders such as Van Zyl Slabbert, among others with ANC leaders which include Thabo Mbeki.

The African National Congress had recently been unbanned; some of its leaders from prison and exile had made public appearances and were now acclimatizing or settling into a jagged-edge society. The release of ANC political prisoners, which started in 1989, would have an almost orchestrated discernible fulcrum moment of February 11, 1992, when the face of the ANC liberation struggle, Nelson Mandela, accompanied by his then-wife Winnie Mandela, was emblazoned on the television screens of the world walking hand in hand out of Victor-Verster now Drakenstein Prison, in Paarl the last place of his incarceration. For the first time, the decades-long banned face of Rhohilahla would be seen, and we South Africans basked in stunned excitement.

When one suggests the ANC ‘gods’ of liberation,’ it is in appreciation that for the first time since the early 60s, Oliver Tambo, Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Wilton Mkwayi, Raymond Mahlaba, Ahmed Kathrada, to name a few of ANC leaders were walking among us. This was also the era when Janusz Walus would dare April 10, 1993, take us to the precipice of civil unrest, if not war, with his broad daylight murdering SACP and ANC leader Chris Hani on April 10, 1993. This particular incident, the full details of who participated on both sides of the proverbial lines of apartheid perpetrator and black masses and victims we may never know, compelled more arduous talks towards the inaugural democratic elections in 1994. It, however, identifies a problem recognition moment.

To underscore my notion of this period identifiable in the ANC gods of liberation, I am reminded of an incident in Parliament where Professor Kader Asmal, a recognized mind in his own right, while serving in the cabinet with Madiba, could not hide his excitement and admiration of Madiba and almost behaved in a teenager sense of excitement as they were lining up to greet Madiba. Indeed the gods of ANC liberation dwelt among us, and even grown ones could not but be swayed in the form of romanticism and euphoria.

This musing will ask what the gods of ANC liberation communicated, meant, and left as an ANC legacy. This four-part musing intends to contend. At the same time, we are often duped into romanticizing the Mandela [ANC gods of liberation] era; we seldom critique it because we are so desperate to be associated with it as a success story when the evidence for its lack of foresight immanent in blind reconciliation agenda trumped apartheid’s black identity marker in rightful justice pursuit. The gods of ANC liberation communicated an ANC membership, and South Africa was star-struck, almost bewitched, until critical assessment left the ANC and its voters.

In a 2015 opinion piece entitled ‘How compromises and mistakes made in the Mandela era hobbled South Africa’s economy’ published in The Conversation, UCT academic Allan Hirsh raises SA’s ongoing economic ill-performance as the premise of some pertinent issues that point to the errors of the Mandela era. Hirsh notes

Established businesses mounted a concerted campaign to maintain the existing structures of the economy. This was an essential item on the agenda of a series of meetings with ANC and other opposition leaders in the 1980s and early 1990s. It is possible to trace some of the country’s relatively poor performance since 1994 to compromises of that era. This demonstrated short-term defensiveness and a need for more imagination about South Africa’s future.

Hirsh furthermore asserts,

In this context, reassuring investors on whom the country was believed to depend was a high priority for the ANC and the new government. What might have been different if the ANC had not constantly looked over its shoulder? Some examples:

- assets such as wealth and land could have been more radically redistributed;

- the Reserve Bank could have been given a full-employment mandate (like the Fed in the US);

- competition policy could have attacked oligopolistic structures, not only anti-competitive behaviour;

- a more vigorous industrial policy might have been introduced;

- small businesses could have had more committed support; and

- the apartheid structure of cities could have been more urgently addressed.’

Perhaps the fundamental point Hirsh makes is that the above interventions ‘were constrained by concerns for economic stability.‘ The idea of referring to these as interventions connotes it is a subject of the leadership better understood in the failure of political leadership. An African National Congress, which claimed it exists for the disenfranchised black masses should have had the presence of mind to initiate the aforementioned interventions.

Fiscal discipline, as led by the ANC, is often nothing more than maintaining the status quo of inequality. This obsession with stability for an ill-structured racialised economy remains the ANC’s bubble. From this false idea of stability, it needs more gravitas in leadership to rethink the role of an SA constitution, the part of the Reserve Bank, the subject of landownership, and the transformation imperative.

While common wisdom will today advocate that we had no option, classic questions we warrant engaging is

- Why did ANC members and voters submit to Nelson Mandela when he, in the heat of Chris Hani’s death, reprimanded them into restraint?

- Would any other subsequent leader of the ANC ever have succeeded or felt entitled to invoke his authority the way Mandela, as representing the ANC liberation gods dwelling among us, did?

- Why did we not question and protest the bad deal of a negotiated settlement?

- Why did we surrender our agency to the political elites on both sides of the railway line?

- Why did we listen to Mandela without asking him what he did daily, sipping teas with white monopoly capital? We all knew he was being softened daily by white economic interest in extensive meetings behind the Development Bank of South Africa.

- Why did we not question the rationale of how poor and unemployed ANC leaders and ex-prisoners all of sudden spent their hours in the company of those who represent the Brenthurst group, were frequent visitors at the questionable Douw Steyn’s residence, and were chauffeured by the white economic interest that had the explicit and planned objective of capturing the ANC with gratuitous favours and shares for spouses and family connected to the very leaders of the ANC?

- Why did we not challenge the financial dry-cleaning of ANC and Tripartite and organized labour leaders who became wealthy and indebted to the white agenda?

- Why were we absent in our critical assessment of an arms deal that until now remains the seedling of the first corruption deal in democracy? After all, it took place in the era of Mandela.

- Why did we not challenge the sunset clause as tabled by Joe Slovo?

- Why did the ANC never rebuke Mandela for agreeing to hand over the Western Cape, placated by De Klerk, who moaned about not having any constitutional power? We know the ANC, led by Allan Boesak, won the elections in the Western Cape. The intervention of now FUL activist Judge Kriegler in cahoots with Nelson Mandela saw to that Pallo Jordan announced that the ANC had lost the Western Cape.

The leadership style and attitude of the ANC liberation gods, as led by Mandela, allowed no natural resistance. Even if it accepted it, the members and voters were too in awe and swayed. Half-inebriated by the euphoria of the ANC liberation gods until dancing the Madiba jive became popular. At the same time, white interest secured its eternity of economic control by buying the very liberation gods, and the people shut up. The ANC’s flagrant unaccountability marked a leadership-uncritical-follower-complex and did not start in December 2017.

I submit that the seeds for what we have in 2023 were sown in this epoch because we failed to keep Mandela representing the ANC liberation gods accountable. Intimidated by the status of being liberation gods, admiration trumped sense, and critical engagement became non-existent. A practice that increasingly would grow from its infancy to the full-grown man we have now with Ramaphosa refusing to be held accountable even by his fellow leaders.

Political Analyst, Theologian, Lifelong Social and Economic Justice Activist, Author, Published Poet and Freelance Writer.